Community membership as a driver of climate action: From rural hunters to progressive activists

By Jessica Love-Nichols, Julia Coombs Fine, Delcia Orona, Forest Ophelia Stuart, Rohit Reddy Karnaty and Shawn Van Valkenburgh, 27 February 2024

Research article

In this paper we show how community membership can motivate climate activism in two very different contexts: for politically conservative hunters and fishers in the western United States, and for progressive climate activists in the US and UK. In the first context, we describe how members of the right-wing hunting community emphasize their collective identity through shared ways of communicating, and as a result, encourage climate activism and challenge the political polarization around climate action. In the second context, we illustrate the importance of feelings of community to experiencing positive mental health effects from climate activism and maintaining the desire to continue participating in activism. This research suggests that, by highlighting collective identities, activists can challenge political polarization and promote climate action even among historically right-wing groups. Furthermore, climate activist groups should cultivate a strong sense of community to ensure that members experience mental health benefits, not detriments, from their engagement in climate action.

Introduction

As the impacts of the climate crisis are felt around the world in increasingly devastating ways, researchers have asked which factors encourage people to take action to confront this crisis. One factor that researchers have examined closely is social identity, which includes membership in broad social categories as well as smaller, more local groups [T. Masson and I. Fritsche, 2021]. In our paper, we consider community membership at both broad and local scales as a catalyst of climate action. First, we examine how members of the hunting and fishing community in the U.S.—people who are generally politically right-wing—experience climate change activism differently when it is framed through rhetoric that highlights their shared experience and how this has led to a budding climate action movement by hunters and fishers in the United States. Second, we introduce new data showing that feeling that you are part of a community is important to young climate activists and their experiences of participating in climate action, characterizing both sustained climate action and mental health benefits resulting from climate action. These studies together show the importance of community membership for encouraging and maintaining climate activism.

Literature review: Identity and climate action

Several aspects of social identity, including gender, race, and political orientation, have been found to impact climate beliefs and actions. For instance, women tend to care about climate change more than men [A.M. McCright, 2010], white men tend to be the least concerned [A.M. McCright and R.E. Dunlap, 2011], and partisan identification has a large impact [D.J. Davidson and M. Haan, 2012]. Political identification, especially, has been shown to be important in influencing people’s beliefs and actions when it comes to climate change, with right wing-identified people typically taking more skeptical stances and participating less in actions to mitigate the climate crisis [R.E. Dunlap et al., 2016]. Scholars have also found that what people call themselves, for instance, “environmentalist” or “activist,” can influence how they engage with climate change politics [C. Brick and C.K. Lai, 2018; C. Roser-Renouf et al., 2014]. In this paper, we explore the importance of community to climate activism within two groups: U.S. hunters and fishers, and progressive climate activists recruited through online forums (mostly from the US and the UK). We use an inductive research design to determine which aspects and scales of community membership are relevant in these two very different contexts.

We further examine the relationship between community membership and the mental health impacts of the climate crisis. Psychological research has found that the climate crisis has negative mental health effects, particularly among youth [J.G. Fritze et al., 2008; H.L. Berry et al., 2010; T.J. Doherty and S. Clayton, 2011]. Emotions like concern, worry, and alarm are especially prevalent [A. Leiserowitz et al., 2018; A. Cunsolo and N.R. Ellis, 2018], and some youth report depression, nightmares, insomnia, and substance abuse [A.C. Willox et al., 2013]. Such research has also shown, however, that participation in social movements can improve climate-related mental health issues [P.J. Ballard and E.J. Ozer, 2016; E.C. Hope et al., 2018; M. Klar and T. Kasser, 2009]. We investigate the importance of community membership to the improvement of mental health through climate action.

U.S. sportsmen

Background

The first group is hunters and fishers in the United States, also often referred to as “sportsmen.” While hunting and fishing themselves are activities that many U.S. Americans participate in—at least 11.5 million people purchased hunting licenses in 2016 [States Fish and Wildlife Service United, 2016], for instance—the hunting and fishing identity is based not only participation in those activities but also a certain cultural affiliation, such as an orientation to firearms, rural and wilderness spaces, and the white working-class and a dislike for urban areas. The majority of hunters in the U.S. are white men over 50 years of age [States Fish and Wildlife Service United, 2016], and the hunting and angling community tends to be politically conservative [Wildlife Foundation National, 2012], stemming in part from their affiliation with rural areas and strong support of firearm access and ties to the National Rifle Association, a conservative lobbying organization. At the recent Hunting and Conservation Expo in Salt Lake City, Utah, for instance, many keynote speakers had been, or continued to be, a part of Donald Trump’s presidential administration, such as Ryan Zinke in 2017 and Donald Trump Jr. in 2018. In 2019 Donald Trump Jr. also spoke along with the Republican governor of Utah. As a community, hunters and fishers have a long history of participating in collective action for the conservation of wildlife and wild lands. In fact, the current version of the “sportsman” identity arose near the end of the nineteenth century primarily as a “hunter/naturalist”—someone who was both a student of nature as well as a hunter and/or fisher [T.L. Altherr and J.F. Reiger, 1995]. Most contemporary hunters, also, are dedicated to wilderness conservation, and there are a great number of non-governmental organizations run by the hunting community that work to conserve and improve wildlife habitat. Because beliefs about climate change in the U.S. tend to be polarized along partisan lines, and most sportsmen identify as politically-conservative, climate change had not, until recently, been a conservation-related issue that many hunters and fishers have prioritized, and many still do not. Several of the hunters interviewed, for instance, stated that the earth was simply going through a natural cycle, pointing to warming and cooling periods previously observed historically.

However, the community has also given birth to an emerging movement for climate change action. In 2009, a number of hunting- and fishing-oriented NGOs created a report called “Beyond Season’s End” for dissemination to Congress as well as the public [“Beyond Season’s End”, 2022]. This report detailed the current and predicted effects of climate change on wildlife species and hunting and fishing opportunities and described suggested plans for both mitigation and adaptation. Since that report, many groups with extensive memberships have begun to focus more on climate change [Jessica Love-Nichols, 2019]. Their efforts include communication (creating media, educating hunters, lobbying politicians, and urging their members to speak to their elected officials), opposition to new oil and gas leases on public lands, and adaptation measures such as fire prevention, wetland creation/restoration, and drought protection. Moreover, the NGO Conservation Hawks was founded in 2011 by a Montana-based hunter and fisher named Todd Tanner. Conservation Hawks pursues the exclusive goal of mobilizing sportsmen to urge action on climate change, has conducted workshops around the mountain west, especially in Montana, and has created extensive media which communicates the risks of climate change to hunters, including a documentary that recently premiered on the Outdoor Channel.

Research methods

To understand how community is important to this emerging climate action movement among hunters and fishers, one author of this research article (Jessica Love-Nichols) conducted 42 ethnographic interviews with sportsmen and women around the western United States focusing on their ideas and actions surrounding environmental conservation. Participants’ political orientation was determined through an open-ended post-interview survey question. In addition, we analyzed the media created by the NGOs espousing climate change action.

Results and discussion

We found that hunter activists drew on a shared sense of community to challenge the political polarization around climate change and urge others to take action on the issue. This strategy has been successfully used by hunters and fishers before, when defending federally-owned lands, another politically-polarized issue (where the Republican party has campaigned to privatize these lands). Navigating this context in support of federal ownership of these lands, one prominent hunting media figure critiqued the polarization, saying, “I’m so tired of that, you guys have heard me go on and on about that, that I come from the party of hunting, fishing, and public access. That’s the only way I approach it.” Around climate action, hunter activists similarly draw on a shared sense of community to challenge the political polarization and urge others to take action.

Activists highlighted their collective hunting identity through three rhetorical strategies common to the community: (1) a performed closeness to wildlife and wild places, (2) an emphasis on experiential knowledge, and (3) a valorization of the past wilderness. In both the interviews and the sportsmen-oriented media, these discourses were used to create doubt and climate skepticism. One hunter and fisher interviewed, for instance, said that he didn’t believe that human activity had caused climate change, and he followed up by emphasizing that he got his knowledge through experience with the natural world while hunting and fishing. He said, “It [climate change] is a natural cycle. You know. We can study it. We can predict it. We can blame somebody. We can’t stop it. There’s nothing you can do but bitch about it. I’m aware of that because I fish. I salmon fish. I’m aware that the fish are coming in later and later every year.”

Increasingly, however, activist groups are using the same rhetorical strategies to emphasize their membership in the community while promoting climate change action. The emphasis on hunters’ closeness to the natural world, their learning through experience, and a nostalgic lens, for instance, are all highlighted in a climate change PSA created by the NGO The Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. This video was created in 2012 and explains several changes that climate change will cause to wildlife and lands in the western United States. It also argues that carbon emissions must be reduced and urges sportsmen to contact their elected officials. The video begins with a view of the moon from space. Sounds of ducks quacking can be heard and then a recording of Neil Armstrong saying, “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Then, in a voice reminiscent of Walter Cronkite-style news anchors, the narrator begins to discuss climate change-related facts. The text suggests repeatedly that hunters are best-positioned to see the effects of climate change because, according to the video, they are the ones “who are most often out on the land,” and are “often some of the first to notice the effects that our changing climate is having on hunting and fishing opportunities.”

Progressive activists in the US and the UK

Background

The second group of people we analyze are activists who are involved with climate-focused communities such as Extinction Rebellion and the Sunrise Movement. We conducted a survey online, and most participants were recruited through climate activist-oriented online forums on the social media website Reddit. The activists who responded were fairly young (the median age was 27), predominantly white (77 out of 107), largely located in the U.S. (64) or the UK and Western Europe (30), lower or middle class (93), and typically characterized themselves as politically left-leaning. Respondents were dispersed across genders, with 54 men, 50 women, and 4 non-binary people. They reported their motivations for activism as arising out of either a moral obligation to act—saying things like “I couldn’t not act” and “I couldn’t live with the regret of not doing my part”— a concern about local environmental changes, including flooding, warmer summers, eutrophication, changing weather, and wildfires, or a frustration with the failure to act on the part of governments and institutions.

Research methods

The online survey contained both multiple choice and open response questions, and covered how participants had become involved in activism, what aspects of activism had positive effects for their mental health, what aspects had negative effects, and what kept them motivated to continue acting. We performed a content analysis of the open response questions to identify common themes in the responses.

Results and discussion

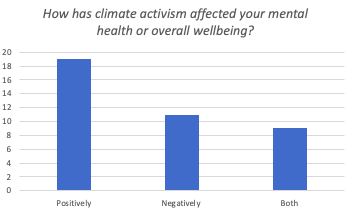

We find that community support helps activists to reap mental health benefits from climate action. Overall, our results show that climate action improved participants’ mental health. Of the 115 participants in the survey, 19 mentioned that climate activism had positively affected their mental health, 11 said that it had negatively affected their mental state, and 9 reported both effects (many responses had to be excluded since participants had misread the question as asking about the effects of the climate crisis, rather than climate action, on their mental health).

Figure 1: Overall results from our survey on how climate activism impacted the participants’ mental state.

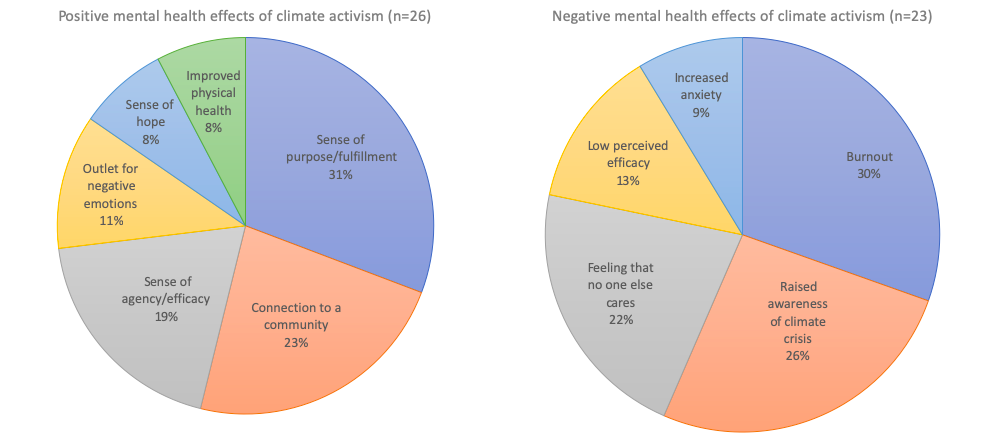

For participants who reported positive mental health effects of activism, one of the reasons often mentioned was feeling connected to a community (Figure 2 left). Feeling part of a community was also linked to feelings of efficacy, or having more power to create change, and activists’ desires to continue participating in climate action. Conversely, feeling that no one else cared about the climate crisis—which could be considered a lack of community membership—was one of the main reasons behind the negative mental health impacts of climate action, as shown in Figure 2 (right).

Figure 2: More detail from our survey on how climate activism impacted mental state. Left: Positive mental health effects of climate activism. Right: Negative mental effects of climate activism.

Conclusion

In this paper, we highlight the importance of community to people pursuing climate activism in two different contexts. In the right-wing context of U.S. hunting and fishing, we find that community membership challenges the political polarization that has historically troubled climate communication. We show how members of this community emphasize their collective identity through shared ways of communicating, and as a result, encourage climate activism among older, white, conservative men—a group that is typically associated with climate skepticism and denial. Among politically progressive climate activists in the United Kingdom and the United States, we find that feeling part of a community is essential for receiving potential mental health benefits effects of climate action; it is also important for maintaining the desire to continue participating in activism.

This research carries two lessons for people interested in promoting climate activism. The first is that highlighting collective identities is vital to promoting climate action among historically right-wing groups. The second lesson is that community membership is important for sustaining climate action among current climate activists, as well as for activists’ overall mental health. Our results show that climate activists can also experience negative emotional impacts from activism and the increased awareness of the climate crisis, but that community membership and shared efficacy can not only be protective against any negative mental health impacts of climate activism, but actually lead to mental health benefits.

One concern stemming from this research is that, at least among certain groups, an emphasis on one community (especially a community that has class or racial privilege) tends to foreground the risks and vulnerabilities of that group, potentially erasing climate injustice and the burden borne by frontline and marginalized communities. While our research shows the importance of community membership and collective identities in encouraging and maintaining climate activism, we recommend that activists keep climate justice in mind and avoid focusing on their own community’s identity and needs to such an extent that there is an omission of the disproportionate impacts felt by marginalized and frontline communities.

- Beyond Season’s End. Adaptation Clearinghouse. Retrieved (2022) from https://www.adaptationclearinghouse.org/resources/beyond-season-s-end-a-path-forward-for-fish-and-wildlife-in-the-era-of-climate-change.html.

- T.L. Altherr and J.F. Reiger: Academic historians and hunting: A call for more and better scholarship, Environmental History Review, vol. 19(3), 39–56, https://doi.org/10.2307/3984911, 1995.

- P.J. Ballard and E.J. Ozer: The implications of youth activism for health and well-being, in: Contemporary Youth Activism: Advancing Social Justice in the United States, J. Conner and S.M. Rosen (Eds.). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 223-243, 2016.

- H.L. Berry, K. Bowen and T. Kjellstrom: Climate change and mental health: a causal pathways framework, International Journal of Public Health, vol. 55(2), 123-132, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0, 2010.

- C. Brick and C.K. Lai: Explicit (but not implicit) environmentalist identity 87 predicts pro-environmental behavior and policy preferences, Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 58, 8-17, https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/84g5v, 2018.

- A. Cunsolo and N.R. Ellis: Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss, Nature Climate Change, vol. 8(4), 275–281, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2, 2018.

- D.J. Davidson and M. Haan: Gender, political ideology, and climate change beliefs in an extractive industry community, Population and Environment, vol. 34(2), 217-234, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0156-y, 2012.

- T.J. Doherty and S. Clayton: The psychological impacts of global climate change, American Psychologist, vol. 66(4), 265-276, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023141, 2011.

- R.E. Dunlap, A.M. McCright and J.H. Yarosh: The Political Divide on Climate Change: Partisan Polarization Widens in the U.S., Environment: Science andPolicy for Sustainable Development, vol. 58(5), 4-23, https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995, 2016.

- J.G. Fritze, G.A. Blashki, S. Burke and J. Wiseman: Hope, despair and transformation: Climate change and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing, International Journal of Mental Health Systems, vol. 2(1), 13, https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-2-13, 2008.

- E.C. Hope, G. Velez, C. Offidani-Bertrand, M. Keels and M.I. Durkee: Political activism and mental health among Black and Latinx college students, Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, vol. 24(1), 26–39, https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000144, 2018.

- M. Klar and T. Kasser: Some benefits of being an activist: Measuring activism and its role in psychological well‐being, Political Psychology, vol. 30(5), 755-777, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00724.x, 2009.

- A. Leiserowitz, E. Maibach, S. Rosenthal, J. Kotcher, M. Ballew, M. Goldberg and A. Gustafson: Climate change in the American mind: December 2018, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven., pp., 2018. Retrieved from https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-in-the-american-mind-december-2018/.

- Jessica Love-Nichols: Towards an Environmental Linguistics: Sociolinguistic Style and Discourses of Conservation among Rural American Hunters and Fishers, PhD Dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, 2019.

- T. Masson and I. Fritsche: We need climate change mitigation and climate change mitigation needs the ‘We’: a state-of-the-art review of social identity effects motivating climate change action, Current opinion in behavioral sciences, vol. 42, 89-96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.04.006, 2021.

- A.M. McCright: The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public, Population and Environment, vol. 32(1), 66-87, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-010-0113-1, 2010.

- A.M. McCright and R.E. Dunlap: Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States, Global Environmental Change, vol. 21(4), 1163-1172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003, 2011.

- Wildlife Foundation National: 2012 National survey of hunters and anglers, National Wildlife Foundation, 2012. Retrieved from https://www.nwf.org/en/Educational-Resources/Reports/2012/09-25-2012-Survey-of-Sportsmen.

- C. Roser-Renouf, E.W. Maibach, A. Leiserowitz and X. Zhao: The genesis of climate change activism: From key beliefs to political action, Climatic Change, vol. 125(2), 163-178, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1173-5, 2014.

- States Fish and Wildlife Service United: 2011 National survey of fishing, hunting, and wildlife-associated recreation: National overview, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Washington, DC, 2011. Retrieved from https://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/HuntingFishingNatSurvey_2012-508(3).pdf.

- States Fish and Wildlife Service United: 2016 National survey of fishing, hunting, and wildlife-associated recreation: National overview, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Washington, DC, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.fws.gov/wsfrprograms/subpages/nationalsurvey/nat_survey2016.pdf.

- A.C. Willox, S.L. Harper, J.D. Ford, V.L. Edge, K. Landman, K. Houle, S. Blake and C. Wolfrey: Climate change and mental health: an exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada, Climatic Change, vol. 121(2), 255-270, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0875-4, 2013.