A month on Arctic ice

No comments yet

As far as the eye can see there is only white, illuminated constantly by light. In these spring nights the sun sets just below the horizon but for an hour or two.

As far as the eye can see there is only white, illuminated constantly by light. In these spring nights the sun sets just below the horizon but for an hour or two.

We are all cocooned inside the sleeping bag of our individual ‘arctic oven’, the only piece of sanctuary and solitary personal space that one has out on the Greenland ice sheet. This is where one airs, literally, their dirty laundry, hanging socks and inner boots by draw stings inside the tents to air out and dry in the frigid arctic air at night.

View of sleeping tents at ‘Swiss Camp’ where researchers spend two weeks every spring on the Greenland ice sheet.

The next morning we rise with the sun high in the sky to resume or start anew various projects and station maintenance required to ensure the camp will survive another winter season standing high on its stilts.

This May, I will be embarking on a science expedition to the Greenland Ice sheet for a month of science, adventure and fun. This will be the 7th time I have been able to partake as a research/field assistant on such an expedition to the Arctic.

The first two weeks are spent at ‘Swiss Camp’, a research station that has been jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and NASA since 1990. The camp is located on the western margin of the Greenland ice sheet, 89 kilometers from Ilulissat (formerly Jakobshavn), Greenland’s third-largest city, at 69°34 N, 49°17 W.

The camp was originally built 1150 meters above sea level, at the ELA (equilibrium line altitude) of the Greenland ice sheet, meaning the snowfall in winter was equal to the melt in summer. Therefore, in theory the surface height at this location should not change from year to year. However, because of the warming that has been occurring in the Arctic, the ELA has moved further north in latitude and this area has experienced significant surface lowering due to excessive summer melt episodes that have taken place in the past decade.

The original camp, constructed in 1990, collapsed in 2012. That spring we rebuilt a new foundational platform at the ice surface for the two tents that remain standing at the location year round (see picture 2 of new platform and tents).

Swiss Camp 2012: New platform for work and kitchen tents that remain erect year round.

The following spring we returned to find the new platform supporting the tents was shockingly above our heads. This was a staggering sight to see, and truly was a firsthand observation of a surprisingly fast warming and the resulting ice loss the Arctic is experiencing.

The ice surface at this location and for a large swath of the southern portion of the ice sheet experienced serious surface lowering. Each spring we return to the same station and each season the station is elevated higher in the air, almost suspended, hovering above the ice sheet on its exposed stilts that once were drilled and anchored into the ice sheet that has since melted out from underneath it (see picture 3: camp platform 4 years after construction).

Swiss Camp on arrival in 2017: roughly 4 meters of surface ice loss here since 2013.

The melting of the Greenland ice sheet has far reaching consequences and impacts the rest of the world. The Greenland ice sheet plays a pivotal role in the world’s climate, not only because of its high reflectivity, high elevation (i.e. as a topographic barrier), and large area but also because of its substantial volume of fresh water stored in the ice mass.

This fresh water, stored as ice, has global implications when it melts for it affects global sea level. Every year the melting Greenland ice sheet contributes roughly 1mm to global sea level rise, and, as recent satellite data shows, this contribution is increasing faster and faster.[1]

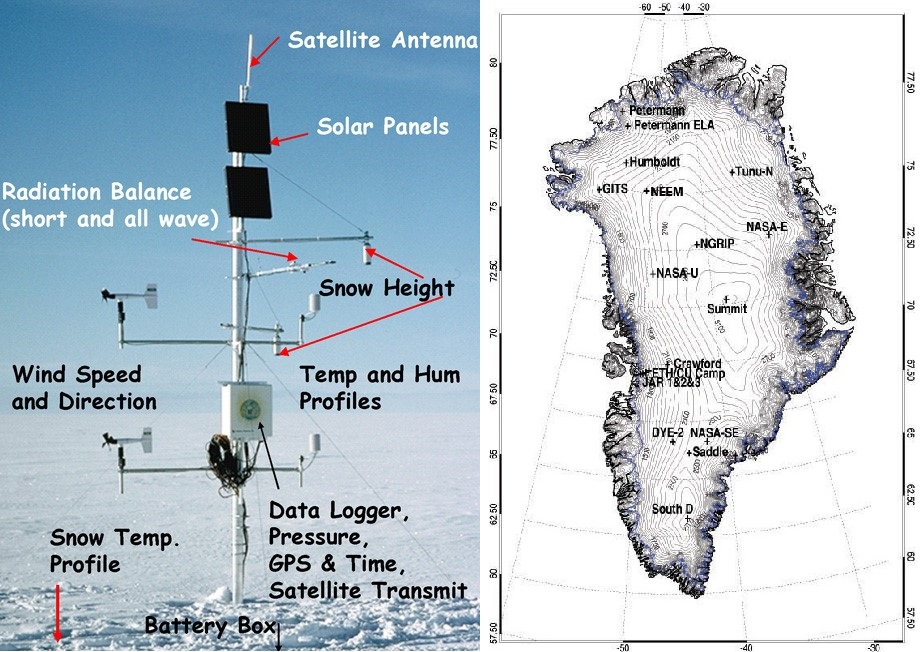

The primary undertaking on this year’s expedition is to service and maintain the Greenland climate network (GCN). The GCN is a collection of 18 automatic weather stations that are dispersed throughout the ice sheet and is representative of the longest running active data set on the Greenland climate.

The first stations of the GCN were deployed in 1995 and they have been continuously collecting climactic data at various points of the ice sheet over the past three decades. The automated weather stations towers consist of two sets of instruments to measure temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction, snow height, atmospheric pressure and a pyranometer to measure the incoming and outgoing radiative heat energy.

The following image is a diagram of an automatic weather station, with all of its corresponding instruments labeled as well as a map of where all the individual automatic weather stations are located on the Greenland ice sheet.

Source: professor Dr. Konrad Steffen, University of Colorado at Boulder.

In addition to servicing, maintaining and updating the Greenland climate network, we will also be carrying out more intensive measurements related to the state of ice sheet. These include monitoring ablation (net ice loss) in the Jakobshavn region, maintaining the collection of Global Positioning System stations and measuring accumulation variability, mass transfer and surface energy balance. The GPS stations indicate that the ice sheets flow towards the Jakobshavn outlet glacier is accelerating, which has serious implications for the mass balance of the ice sheet for this accelerated flow means that more ice is lost at the terminus of the ice sheet through iceberg calving.

In addition to the science that will be conducted this spring field season, a new project between myself and Climanosco will be to conduct a number of interviews with the various international scientists and local experts about their experiences living and working in the Arctic. I’m excited to discover what motivates them as they live and work and consider climate in one of the world’s harshest environments. We’ll be sharing their reflections and insights over the coming months, so stay tuned!

Immersing myself in local customs, dog sledding in Qaanaaq, North Greenland.